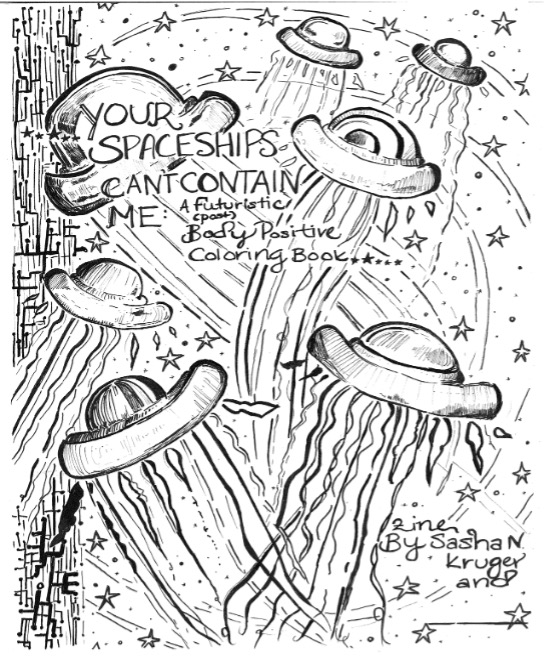

In the Spring of 2016 in the course “Visionary Medicine: Racial Justice, Health and Speculative Fictions,” taught by Professor Sayantani DasGupta at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, I produced a zine called

Your Spaceships Can’t Contain Me: A Futuristic (Post) Body Positive Coloring Book. The following year, it was displayed at the NYC Feminist Zine Fair and in an art exhibition at CUNY called “Zines as Creative Resistance” (Clyde and Bakaitis 2017). Whilst not part of the exhibit or within the physical copy of the zine, I wrote a process paper that charted the thinking behind its pages.

In 2022, thankfully (1) the movement of Fat Liberation presses on, continuing to bring to the fore the limitations and inherent tensions within the framework of Body Positivity, or what some call #BoPo and subsequently BoPo.2. Likewise, the interest, engagement with, and publication of speculative projects, papers, panels, and futuristic Third World fictions have exploded, amplifying the ongoing significance of this artistic experiment: an imagined future writ in the past, and a request to co-create the zine with my readers, together.

I am grateful to the scholarship of Sabrina Strings, Da’Shaun L. Harrison, Virgie Tovar, Caleb Luna, and the activism and art of so very many more.

(Afro)futurism, Latina/o/x and Indigenous futurity, and affiliated speculative strategies, in their quests to imagine and project marginalized, underrepresented peoples into the future, can also be considered a praxis of body positivity. In its current historical iteration, body positivity emerged as a counternarrative to fat phobia: one that seeks to delink health (and stigma) from body size. Recognized today as a cultural movement, body positivity espouses self-love, self-care, and the belief that “all bodies are good bodies.”

While the movement (2) has been challenged for its antithetical investment in representing white, thin cis women existing, loving, and accepting themselves and its narratives criticized for its black, brown, and trans exclusivity (3) , the concept behind body positivity is not entirely new. From the celebratory slogan “Black is Beautiful” to the vehicle of ‘rehoming’ one’s body as a means of self-reclamation in

diasporic literature, claiming the space of representation and self-worth in the face of body-devaluation are revolutionary acts of the past and present. Body positivity, as a potential decolonizing modality, is, thus, a part of radically envisioning new health futures today.

In this reflective essay, I explore how one might communally imagine and create a (post) body positive future through the genre of an affirmations coloring zine. Because postcolonial speculative modes of narration are concomitant with imagining body positive futures—those alternate ways of existing (and relating) outside of the bounds of oppression— I employ an aesthetic to help engage with body-positive concepts projected into (uncertain) universes.

I Am a Unique Being in the Multiverse

(Pg. 1 Zine)

What does body positivity look like in the context of a post-alien/post-human future? The term post-human helps us rethink the category and position of humans as the epicenter of the moral world. Post-alien refers to an imagined time where all possible modes of being in any dimension or realm cease to be de-familiarized, other-ed, or made foreign. As Jessica Langer asserts in Postcolonialism and Science Fiction, “Although this concept of alienness does not always signify a colonial relationship, it often dovetails with the colonial discourse of the Other” (82).

What, then, does representation for all bodies mean if the whole cosmos is at play? How might one practice a futurity (in the present) wherein all bodies are valued and accepted—if that is body positivity’s sole telos? In my first drawing and throughout much of the coloring book, I not only struggled with illustrating body positivity for entities outside of the constraints of human convention but with representing “alien” beings as well. Like Greg Van Eekhout in his short story “Native Aliens” and Octavia Butler in Bloodchild, I grappled with what we and other life forms could look like in the future. Since body positivity at this time encourages representation as its principal approach to securing a positive body image, I offer optional places for the participant to render themselves in the delineated scenes. Rather than an exercise of identity tourism (4) —assuming another race/ethnicity/gender/sexuality/class/culture and/or unfamiliar embodiment as a form of recreation or for voyeuristic teaching purposes—I aim to create space for colorists to envision their own stories and self-determine their own futures within the zine’s bounds.

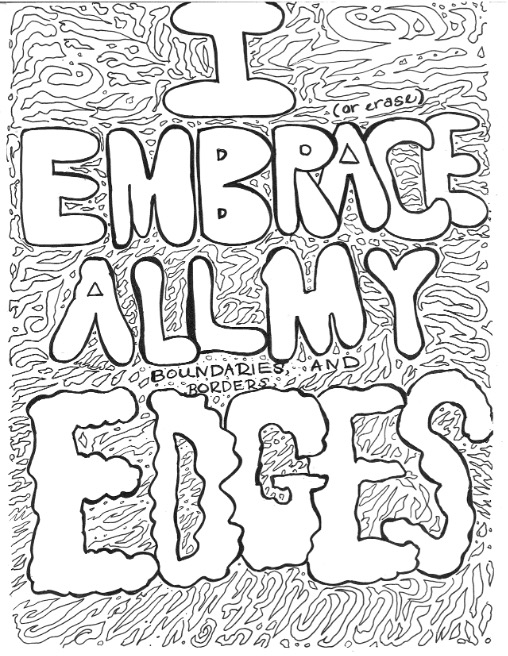

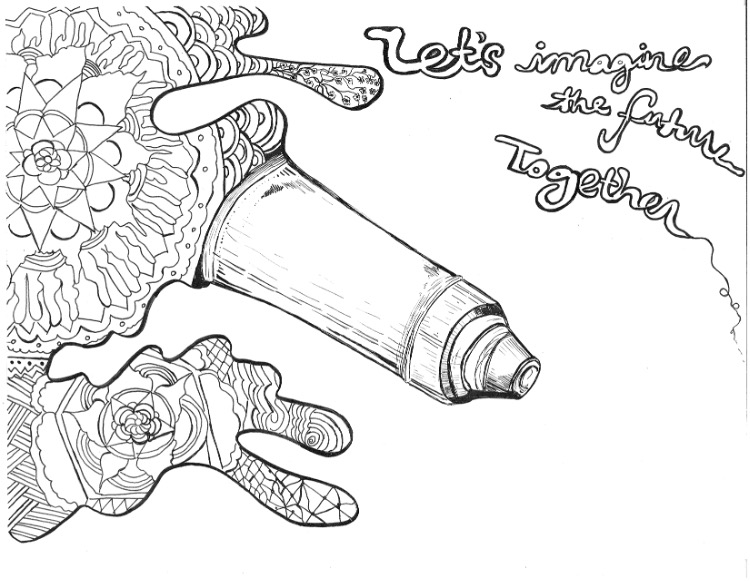

I Embrace (Or Erase) All My (Boundaries, Borders), and Edges

(Pg. 3 Zine)

Many body positive quotes welcome the body’s boundaries and its curved edges. While Gloria Anzaldúa and Walter Mignolo speak about the violence of borders as well as border-consciousness’s promise of decolonial thought, is body positivity in the future an erasure or celebration of each other’s presumed margins (387, 199) (5) ? In other words, where does my body begin and yours end? Also, where does my body positivity begin and yours end—here or in another future? In that light, does one’s beginning necessarily mean another’s end?

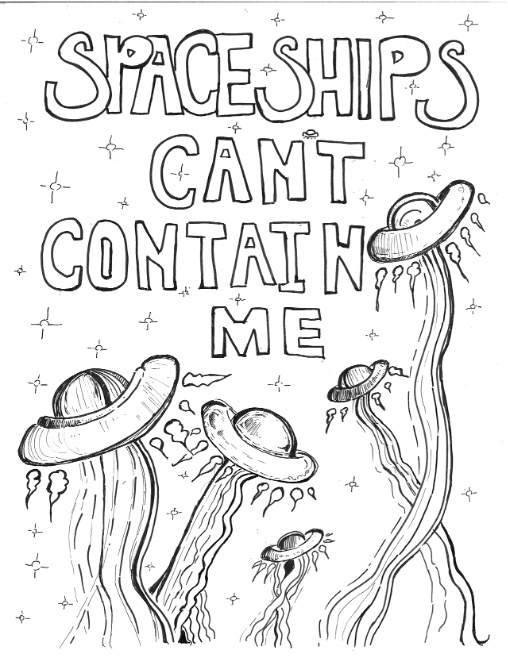

Spaceships Can’t Contain Me

(Pg. 3 Zine)

In page three of the zine (image above) and throughout the booklet, I widely adopt themes of space—common tropes in speculative science fiction. Addressing the subject matter of space in Afrofuturist practice, Ytasha L. Womack elucidates:

Whether it’s outer space, the cosmos, virtual space, creative space, or physical space, there’s this often-understated agreement that to think freely and creatively, particularly as a black person, one has to not just create a work of art, but literally or figuratively create the space to think it up in the first place. (142)

Both imagination and body positivity are spatial endeavors. Although spaceships are vessels that can carry us “toward[s] a new identity, a new aesthetic practice, and perhaps, finally a truly new future,” I have the zine’s colorists refuse any spaceship other than one of their own making (“Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, and the History of the Future” 5). I assert alongside my artists the right to take up space as well as reject any attempts imposed by other beings (including myself) to circumscribe their imagination or existence. With your own spaceship, you can escape the parameters of another’s.

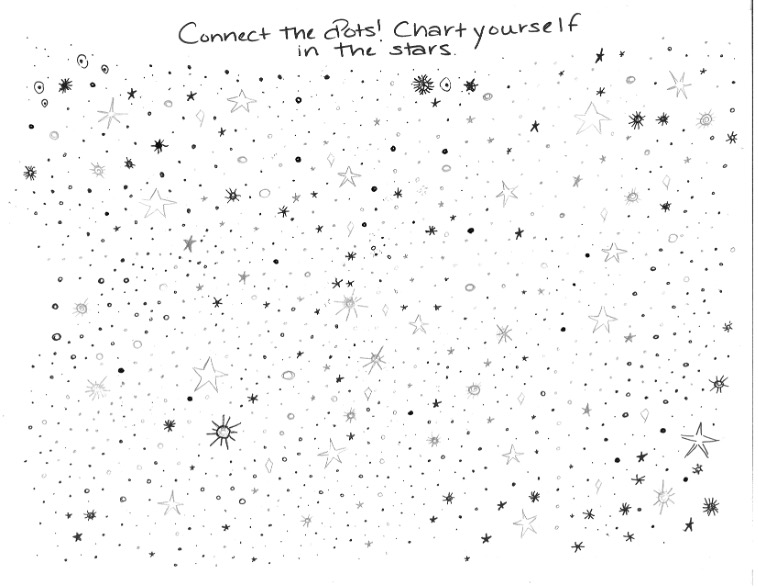

Connect the Dots! Chart Yourself in the Stars.

(Pg. 4 Zine)

On page four, I examine how zinesters might use the pattern I provide in generating their own images. I am fascinated by singer/songwriter Erykah Badu’s analogy of star-charting as a modality for self-recovery and repossession in her music video “Didn’t Cha Know.” I therefore decided to create this page to explore agency within the genre of coloring books, which are themselves experiments in power. One can decide to color inside the lines or outside of them; one can distort or exaggerate a form’s usual hues.

Most connect-the-dot exercises give you a predetermined path to illustrate, which maps “the networks of power that would propel [us] into various futures not of [our] own making,” (“Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, and The History of the Future” 5). Instead, this activity has no fated design. We connect the dots to reimagine a past as a way to participate in the future.

Let’s Imagine the Future Together

(Pg. 5 Zine)

In “Imperialism, the Third World, and Postcolonial Science Fiction,” authors Ericka Hoagland and Reema Sarwal suggest that sci-fi engages with a dialogue or dialectic that, “encourages the reader to reexamine both the world and herself. Viewed dialectically, then, one reads science fiction and is also read by the genre” (12). Hence, can a (post) body positive future be realized through its co-construction? Coloring books are collaborative acts—ones that depend on the colorist as much as they do on the artist who prescribes the lines. I cast kaleidoscopes as the technology for envisioning and its mandalas as a metaphor for speculative practice. No two designs fabricated by the kaleidoscope will ever be alike; once rotated or shaken, their seemingly endless refractions and patterns will never be arranged in the same way. Like sand mandalas that are coproduced (and ritualistically dismantled once they have been completed), in this image above, I incorporate the mandala as a symbol to liberate the future I depict. However, just because I drew it, doesn’t mean it has to exist.

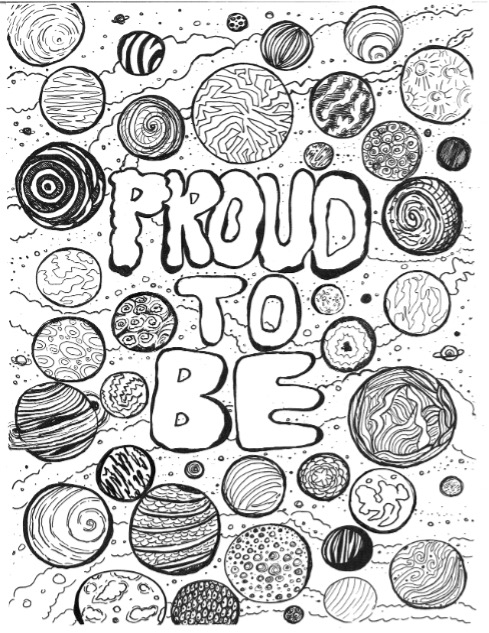

Proud to Be

(Pg. 6 Zine)

Pursuing modes of existence and relation beyond anthropocentrism is a decolonial act. According to Walter Mignolo, the process of decolonial healing is “that of becoming a decolonial subject or ‘learning to be’” (199). If all bodies are represented, acknowledged, and valued, is existence—to be—body positivity’s source of health in and for the future? Coloring books are now considered to have therapeutic potential: “Adult coloring works similarly to meditation and helps colorists block out negative thoughts” (Dovey). Thus, by allowing us to focus on the moment—a ‘learning to be’ if you will—coloring becomes a way in which the present may be reconfigured while visualizing (and coloring) and being in the future (Womack 147).

Affirm Anew

(Pg. 7 Zine)

My final page prompts the readers to devise their own body positive affirmation as a way to conceive of a future they want to romance. Affirmations “emphasize the power of thought to create reality,” which is critical to futurist methodologies (Womack 79). Liberatory futures are also contextual to the individual and community that imagines them. For some, the setting of the future is in reclaiming the past. In this sketch, the moon phases delineate temporality whilst the expanse of the page opens up the possibilities for its co-creators to imagine an entirely different setting in which they would prefer to envision themselves—locations other than starry nights and spaceships anon!

Seeking Liberation “Scattered Across the Stars”

To situate body positivity into some unknown future allows us to disrupt body positivity as it currently stands as well as critically reflect on its restrictions as an avenue for imagining health futurity today. However, there are many problems in my attempts to imagine what (post) body positivity would look like in the future. Most of my images use landscapes of outer space, which can easily become imperialist ventures and echoes of settler colonial desire: “As Gregory Benford describes as the ‘Galactic Empire motif,’ the concept of a human empire of many planets, scattered across the stars […] ‘There are generally no true aliens in such epics, only a retreading of our own history’”(qtd. in Langer 83).

In fact, the language by which I imagine such body positive futures “for all” is limited by idiom itself. The zine’s methods are also intermedial in nature: It can be read visually as well as textually. For example, all beings do not know verbal language, nor is it probable that they read and draw as methods of communication or have individualistic self-concepts and subjectivities. The question remains, is the motive for imagining a (post) body positive future utopic (hence dystopic)? And is depicting a mandala an orientalist and appropriative endeavor? Undoubtedly. The use of stars, too, could be viewed as problematic given their connotation with meritocratic capitalism in the classroom.

Nevertheless, the strength of zine-work is in making accessible knowledge-production—pursuits integral to any real praxis of body positivity or futurity. Part of Fat feminist speculative practice is an undertaking of thought experimentation as exploration; ironically, sometimes our imaginations cannot liberate us in the way that we had hoped.

(Back Cover, Zine)

Works Cited

“Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, and the History of the Future.” Journal of the

Research Group on Socialism and Democracy 20.3 (2011): n. pag. Web. 9 Feb.

2016.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. “La Conciencia De La Mestiza/Towards a New Conciousness.”

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Meztiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books,

1987.

Clyde, Wanett I. and Elvis Bakaitis. “Zines as Creative Resistance—Exhibit.” New

York: City University of New York, 2017.

Dovey, Dana. “The Therapeutic Science of Adult Coloring Books: How This

Childhood Pasttime Helps Adults Relieve Stress.” Medical Daily. IBT Media

Inc., 8 Oct. 2015. Web 17 Apr. 2016.

Gaztambide-Fernández, Rubén. “Decolonial Options and Artistic/AestheSic

Entanglements:i An Interview With Walter Mignolo.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3.1 (2014): 196-212.

Hoagland, Ericka and Reema Sarwal. Introduction. Science Fiction, Imperialism and

The Third World: Essays on Postcolonial Literature and Film. By Hoagland and

Sarwal. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2010.

Langer, Jessica. Postcolonialism and Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2011.

Womack, Ytasha L. Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture.

Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013.

1. I am grateful to the scholarship of Sabrina Strings, Da’Shaun L. Harrison, Virgie Tovar, Caleb Luna, and the activism and art of so very many more.

2. Fat Acceptance and its associated movements were largely led by and appropriated from women of color: “The body positive movement was created by and for people in marginalized bodies, particularly fat, Black, queer, and disabled bodies” (Qtd. in Gulino 2021). See “Body Positivity Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Does” Vice Media Group. Refinery 29.com. 25 Mar. 2021.

3.Finch, Sam Dylan. “4 Body Positive Phrases That Exclude Trans People (And What To Say Instead.” Everyday Feminism Magazine. EverdayFeminism.com, 17 Mar. 2016

4. A term defined by Lisa Nakamura in her work Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet (2002) and discussed in Chapter Three of Langer’s Postcolonialism and Science Fiction: “Race, Culture, Identity and Alien/Nation.”

5. In “La Conciencia De La Mestiza/Towards a New Consciousness” and “Decolonial Options and Artistic/AestheSic Entanglements: An Interview With Walter Mignolo” respectively.

|